In response to various requests, I’m making available the manuscript of my Plenary Address to the Ecumenical Youth Pre-Assembly of the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Karlsruhe, Germany, on August 26th, 2022.

While the text that follows is not a sermon, I prepared it to be delivered in that mode. Thus, the document reflects my preaching and speaking style. I wrote the text to be heard, not read. The grammar and punctuation match the document’s initial aim. Undoubtedly, much of what I actually said cannot be found here, but the main ideas and general thrust of the text are consistent with the spoken word.

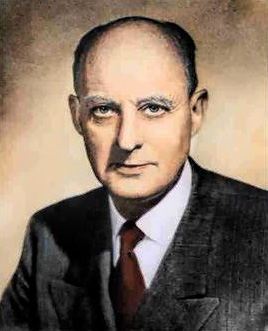

Photo Credit: Ecumenical Youth Gathering, World Council of Churches

I wonder, during your time together, have you all discussed the fact that, in the ecumenical movement, the term ‘youth’ tends to include a whole mess of people?

Folks are called ‘youth’ from the time they become teenagers to the time they hit thirty-five (and sometimes people even fudge it and make it forty)! I have found that, at least in my region, you can judge where someone is on the spectrum of ‘ecumenical youthfulness’ by the kind of computers they used growing up.

Now, I’m only thirty, and when I was younger, I had my own computer, but it was the kind that many of you would probably go to see in a museum. It was huge, bulky, and horrendously slow.

One of my most formative teenage memories occurred in front of that big old beast of a computer. After school one day, the rest of my family went out for some event, but I stayed home to finish my schoolwork. For once, I was alone in the house. I clicked my way to YouTube. Fearful that someone might see what I was watching, I minimised the window to the smallest it could go. By the time I finished manoeuvring the window, it was a tiny square in the right-hand corner of the big screen.

I was terrified. My heart was racing!

I put on my headphones and clicked the play arrow. I paused the video, which was several years old by then, every few seconds to check over my shoulder at the door or look out the window to check the driveway—I could not risk anyone seeing what I was watching.

So, with trepidation and in fits and starts, I watched as the Vicky Gene Robinson was consecrated as the Anglican Communion’s first openly gay Bishop.

I also watched a news real in which Robinson read a few of the death threats he had received in the days preceding his consecration. I watched as the cameras panned over the mass of angry protestors calling him every name in the book. I watched as Robinson added a new liturgical vestment to the ensemble when he lifted a heavy bullet-proof vest over his shoulders and tried to cover it with his Alb prior to the worship service.

The organ started playing, and the precession began. Tears filled my eyes as the historic symbols of his office—the stole, the ring, the mitre, the chasuble, the staff — were conferred upon him.

I was terribly afraid yet filled with hope.

I am not even an Episcopalian and I did not understand why someone needed to wear all that fancy stuff just to be ordained; Even so, I was enwrapped by a feeling of embrace and acknowledgement that I had never before experienced.

Photo Credit: Ray Duckler, Concord Monitor

For the first time I can remember, I bore witness as the church affirmed God’s call upon the life of someone like me. For the first time, I came face-to-face with a possibility I had never before envisioned. I came to know the profound truth that one can be both openly gay and faithfully Christian at the same time.

I’ve encountered God many times on life’s road, and the scales have fallen from my eyes more than once, but I will never forget Gene Robinson’s courageous witness as he took up the bishop’s mantle.

By simply being who he was and living as God called him to live, he let a little light shine and enabled me to catch a secret glimpse of a different world and a brighter future of healing and hope, not only for myself, but also for the church.

I grew up in a fundamentalist tradition. The institutions of which I was a member had many lists of people and groups they thought God had called them to exclude. In truth, pretty much everyone with whom we disagreed was bad, but being gay was the worst thing you could be. Perhaps because of where my faith journey began, rather than in spite of it, I set out on a journey to understand what scripture and the church’s tradition have to say both about me and to me.

I was a long way from embracing who I am as a gay Christian back then. So, perhaps I did not consciously set out in search of some enlightened goal of self-actualisation. More than anything else, I suppose, I believed that, if I were to ask real questions about the concerns that dominated my life, I might as well start with the sacred texts and beliefs to which so many of the faithful people around me turned for guidance.

The road toward a deeper understanding of God’s call on my life was a bumpy one, especially in the beginning. Yet, even as I dedicated myself to the vein search for security that so often characterises the fear-filled world of fundamentalism, God’s grace continued to break down the doors and call me home.

These days, I spend most of my time studying the church’s history. I am regularly in awe of how our faith communities exhibit both the potential to change the world for the better and the capacity to inflict deep and lasting wounds.

I know this is not exactly a great advertisement for ongoing involvement with ecumenism, but here is a secret that is often kept from young people at gatherings like this: Though there is nothing more beautiful and enriching than being part of this movement when it lives up to its stated values, the deeper you get into the life of the world church, the more astonished you will be by its humanity – by its brokenness, by woundedness and capacity to wound.

The church is filled with people from across the world who call themselves siblings in Christ. The church is that one place where many of us have felt fully known, wholly embraced, and absolutely secure in the loving arms of a saviour. Yet, for all its warmth and holiness, it is also a place where we can experience real violence.

Like an abusive friend or loved one, the church can cut you to the bone and then, lest you seek a soothing balm elsewhere, offer you a tattered bandage to suture the wounds it plans to inflict upon you again in the future; This is especially true if something about you does not conform to what some people say a Christian should be.

The church is a gift from God to the world, but in its institutional, historical, empirical, and (YES!) political form, it often feels like anything but a foretaste of heaven.

The church may be eternal, as some of our traditions suggest, but it also exists within the confines of history, and human sinfulness mars any attempt to perfect unity, equality, or justice within its institutions and councils.

Some of you, perhaps even most of you, may come upon moments in your life in which you feel called to follow a path trodden by many before you. Perhaps you will come to a point at which you believe you must leave the church to find God.

Today, you might critique the theology of such a statement, but I caution you, tomorrow you may find that it speaks to the depths of your wounded soul. If I happen to be with you when such a moment of pain comes, I will not try to put a dirty, warn-out old bandage on your wounds. I will not try to sell you some cheap hope to numb the pain and hush the anger so that you and our world can be wounded again, and again, and again. I will only tell you what I believe.

I believe that, in spite of its constant failures and the increasing irrelevancy of its dialogue, the values enshrined in the church and, by extension, the ecumenical movement; the values of unity amid diversity, diakonia amid difference, and the promise of just reconciliation in Christ are the world’s last best hope.

Whether you agree with me on the questions facing the world church or not, this movement needs you. Not just your free time or a few weeks this summer– It needs your life and your faithful witness to Christ so that it can more fully realise his mission. It needs to be confronted with your stories of pain, and anger, and frustration, and joy, and hope, and love.

For those of you who have been and continue to be wounded by the world church, I cannot, and I will not ask you to stay in an abusive relationship. Once again, all I can do is tell you of a promise in which I trust.

I trust that wherever you find yourself on the spectrum of ecumenical youthfulness and wherever you fall on life’s other spectrums, you are not alone.

God sees your wounds, even if the church closes its eyes. God hears your cries of anguish, and pain, and righteous anger at injustice, even if the church covers its ears. God’s heart breaks when yours breaks, even when the church’s heart is hardened.

In life, and in death, and everywhere in between, whoever you are and wherever your journey started, whether your pastor, or your priest, or your bishop, or your church, or your family, or your friends—whether anyone else supports you or not – you belong to God, and God will always be there to welcome you home.

Amen.