The train ride along the Rhine from Bonn to Bingen transports me into the land of fantasy. I imagine that Esgaroth might lie around the next bend, with Rivendell to follow beyond the distant mountains.

It’s much more likely that the curious traveler who sets out in search of imaginary lands will bump into a factory or a car dealership; A disappointing taste of reality for those who are easily caught up in fairytales.

I sojourned to Bingen a few months ago after getting on the wrong bus. My goal was to visit a new church in Bonn, but I ended up traveling out beyond the city. Refusing to waist a Sunday morning, I found the next train station and checked the map for possible destinations. Bingen was less than two hours away!

I first heard of that ancient German village when I was in seminary. I was introduced to Hildegard von Bingen in a class called “Women Leaders of the Medieval Church.” I fell in love with her writing, worldview, and passion for life. The following summer, I read as many of her works as possible.

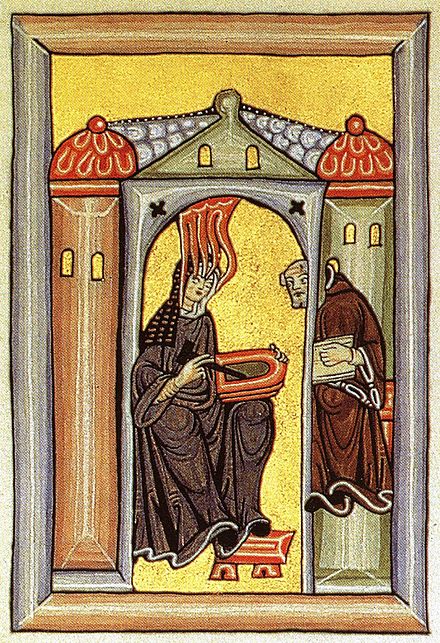

Hildegard, also known as “Sibyl (oracle) on the Rhine,” was a twelfth-century abbess of the Benedictine Order.

She was also a mystic, musician, theologian, medical practitioner, and natural scientist. Her works weave monastic theology, religious extasy, and observational science together in a paradoxically simple and complex web of self-reflection. During her life, leaders and other notables journeyed up the Rhine from across Christendom to seek her counsel.

I stepped out of the Bingen train station to find a typically modern german town. Noticing the empty streets imposed an annoying realization on my psyche; I should have checked if anything would be open on Sunday before jumping on the train!

Disappointed, but determined, I trekked up the lonely streets until I stumbled upon an old stone church rising out of the mist.

The efficient style of modern architecture that surrounds its humble spires pulls the traveler in an unwanted direction, away from the “all verdant greening” that was both the nexus and inspiration of Hildegard’s thought. This nineteenth-century structure, like its siblings around the town, resists the strain. It pulls the visitor back into the worldview of a mystic, in which the impossible is only that which is still coming to pass.

For Americans, the construction of the contemporary beside the classic in both architecture and thought is somewhat startling. We appreciate dichotomies; Even when we challenge them. Our cities reflect a desire to confine what is ancient to the dead spaces of museums and historical walking tours so that our vision of modernity might not be complicated by remnants of another way of life. In most of the world, such dichotomies are impossible. Things are simply too old, and histories are too long to be made perpetually new.

I suppose my dichotomous American worldview kept me from seeing its own gravest corrective on the way up the hill toward the church.

My perception was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that I had been nursing a cold for over a week before setting out on the day’s journey. Yet, I can’t shake the feeling that what I saw carried an easily overlooked significance. After completing a self-guided tour of the site, I relatched the church yard’s heavy gate and turned to go down a new street. Realizing that I had forgotten to reset the drop rod, I turned around and was surprised by what I saw accross the way.

Hildegard’s Apotheke (pharmacy) is a bridge between that which we call “pre-modern” and the things we deem “contemporary.”

The store was closed, so I didn’t get a chance to ask its proprietors why they chose to name their business after the town’s most well-known citizen. If I had gotten the chance, I pray their answer would have pointed to a deeper motive than the desire to capitalize on a local hero’s legacy. Whatever their inspiration, the decision to name the store in honor of Hildegard reflects at least some awareness of who she was and how she lived. It captures her ability to bridge the imaginary divide between the pains, frustrations, and ailments of life in the world and the life of the soul.

Truth be told, it is difficult, perhaps even impossible, for me to see the world through Hildegard’s eyes.

With Calvin, I can speak of creation as a theatrum glorea, because his image is built upon the assumption that a playwright who knows the plotline sits behind the curtain, guiding the external manifestation of his vision toward its telos. The image of a God who is “other;” who is unmoved and incapable of being caught up in the vagaries of human existence is comforting. At least someone has it all together!

Hildegard’s thought patterns are different. They are alien to the Reformed rationalism that shapes my modernist worldview. They make me uncomfortable. She sees divine presence in everything. God pulsates through creation giving life to life within the cosmic embryo that is God. The image of nature that she paints fills me with awe. I am drawn to her world like a sick person to a pharmacy. I may not understand why, but I feel there is something within it that promises a cure; For what, I am not sure.

I need Hildegard and people like her in my life. I need to be confronted by thought patterns that turn my assumptions about the machinations of the world into questions about the nature of reality.

Perhaps there is wisdom to be found in what is old; In the things that existed before tract housing, plaster casting, and the readymade uniformity that so characterizes an age defined by its longing for the shallow freedom of individuality.

View of the Basilica of St. Martin of Tours from the Nahe

Print of Hildegard from Wikimedia Commons. All other photos were taken by the author.